Clive Cowdery is arguably the most influential non-politician in UK politics today. His proteges at the Resolution Foundation, a think tank he founded 20 years ago, now staff the halls of Westminster and its ideas occupy the minds of Labour’s government ministers.

While Resolution is largely seen as leaning to the left, Cowdery — an insurance entrepreneur whose £200 million ($267 million) fortune belies his impoverished upbringing — remains a champion of markets.

“Capitalism is the only model we have found for generating the kinds of returns which, provided it’s linked to a proper redistributive system, can help lift people out of poverty,” he says, sitting down for an exclusive interview with Bloomberg.

Resolution’s mission is to raise living standards for the people “we used to call the working poor,” he adds — those who have jobs but still struggle to make ends meet. It’s a demographic that has attracted increasing attention from political parties in recent years, one marker of Resolution’s success.

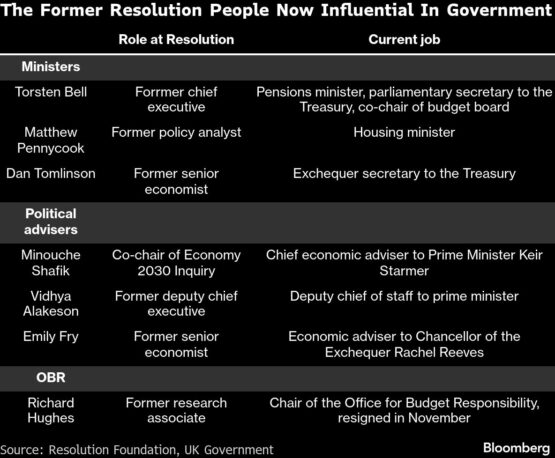

Another is the journey several of its top experts have made into the heart of British political decision-making. No fewer than seven Resolution associates have found themselves in senior government positions, five appointed since Labour’s election victory in 2024. They include former chief executive Torsten Bell who oversaw last month’s budget and has become a powerful cross-departmental pensions minister.

The road from Resolution to Whitehall continues to be walked, with Emily Fry, an economist at the group, appointed as adviser to Chancellor of the Exchequer Rachel Reeves in October, during the frenetic, late stages of the budget’s construction.

The biggest furore around the budget stemmed from Resolution’s office. When Reeves gave an unusual television address to the nation in early November, she seemed to be laying the ground for a manifesto-breaking rise in income tax, with reports that National Insurance — a payroll tax — would be cut to make up for it. The so-called “two up, two down” plan was ultimately dropped over the potential cost of breaking an election promise.

“Don’t break my heart,” Cowdery says, when the subject comes up. “How progressive would that have been compared to what was announced, hey?”

He is clearly disappointed the budget, which Bell had such a hand in shaping, was not more ambitious, but refuses to be critical of the government.

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

Persuasion

Despite the personnel moves, Cowdery doesn’t accept that Resolution is more influential than other research groups like the older, respected Institute for Fiscal Studies. It just takes a different approach, he says, as a “think-and-do tank.”

A decade ago, he moved Resolution’s office to Queen Anne’s Gate in the heart of Westminster, putting his organisation “within sight of the target,” as he puts it, gesturing at the UK Treasury building a stone’s throw away on the corner of St James’ Park.

A pub called the Two Chairmen, a few paces from its front door, is the Treasury’s local drinking hole, where Reeves celebrated on the evening of the budget. Resolution is literally on the doorstep of the power it hopes to shape. “I’m not interested in just putting ideas out,” Cowdery says.

Paul Johnson, who ran the rival IFS for 14 years, notes that Cowdery’s team “did more advocacy, spent more time in Whitehall — they were more deliberate in their engagement with MPs, Labour MPs in particular.”

It doesn’t hurt having a deep-pocketed benefactor, of course. Cowdery has put more than £80 million into the Resolution Trust, which funds the foundation’s work. Johnson can barely hide his envy. The IFS may have three times Resolution’s £3.7 million annual budget and more than twice its 30 staff, but it has to chase donor money and deliver client project work. Resolution’s superpower is its singular focus.

“That is why we’ve been successful,” Cowdery says.

While other wealthy Britons choose the direct route to political influence, like crypto investor Christopher Harborne’s £9 million donation to Nigel Farage’s populist Reform party, Cowdery takes a subtler course.

Generating ideas for debate via a think tank creates “air cover” for better government, he says. “The brave men and women in politics can only act within the headroom of what are publicly acceptable ideas. If they can’t be envisaged, they can’t be acted on. And no politician can act in advance of where the public has got to.”

Humble beginnings

Cowdery, 62, built his fortune with Resolution Life, which he set up in 2003 to buy closed life insurance funds, drive efficiencies and reward investors with steady returns. He turned the business into a £5 billion FTSE 100 company, which he sold in 2008 before repeating the feat with Friends Life, which was acquired by Aviva for £5.6 billion in 2015. In October he offloaded his final interests, all overseas, to Japan’s largest insurer Nippon Life.

ADVERTISEMENT:

CONTINUE READING BELOW

His financial success is a reminder that Cowdery is a champion of capitalism, for all his proto-socialist principles and lifetime interest in Soviet-era art.

Where capitalism fails, he argues, is during periods of intense change. On a visit to the People’s Museum in Manchester several years ago, he left in tears, he says, after following the story of industrial transformation from the spinning jenny to the modern day. “You watch industry by industry rise and affect vast swathes of people – and you don’t want to stop that, but will we never learn how to transition people?” What upset him was “policy, failure to plan.”

To understand why he is so affected by such tales, it helps to know Cowdery’s origins. Raised in Bristol, in England’s west country, as one of five children by a Danish single mother with drug addiction, he and his siblings bounced through 19 different care homes, living in bedsits and on the streets, until Cowdery and his elder brother Steve were taken under the wing of a Christian family in North Somerset when he was nine.

Cowdery’s eyes fill as he recalls the 71-year-old “tall, thin, silver-haired, courtly” Doctor Spence in Bristol’s affluent Clifton district who refused to give up on them, withholding the state-supplied two-week course of pills on which his mother overdosed numerous times — releasing them to her daily instead, until he found their new home.

The family that took in him and Steve, which their mother would later join after an overdose that hospitalized her for 11 months, was deeply Christian and the church would shape his young life. He married, had children of his own and moved to a branch of the church in New York State in the US before returning to Cornwall.

It was in Ronald Reagan’s America and Margaret Thatcher’s Britain that he saw it wasn’t just penniless families on welfare like his that were struggling but working families who could barely survive on the income they brought home. That sense of injustice stayed with him, sowing the crusading seeds for Resolution, even after he lost his faith and left both the church and family in his late 20s to start again as a door-to-door insurance salesman, later remarrying and becoming a father once more.

He won’t discuss family, deflecting instead to his loss of faith. “All that happened is in my late 20s I grew up, and I began to separate the social desire to help from the religious desire to convert.” Or perhaps his faith simply changed. In economics he has found a new liturgy, and in Resolution he has a pulpit.

‘Propaganda by explanation’

Despite being a “grateful beneficiary” of welfare, Cowdery is more concerned about working people. We need to “address the size of the state” because it has become unaffordable – particularly the cost of working-age health benefits that the OBR estimates will increase by £18 billion over the next five years to £80.2 billion, he says.

“We understand the role of disability support. It’s just that we are hard-headedly aware that on this current trajectory, the country will not be able to afford future projected bills that come from that.”

Cowdery’s political interests stretch beyond Resolution. He owns Prospect magazine, with its long-form essays, and has a stake in The Observer newspaper. He compares their content to what The Observer’s great editor David Astor called “propaganda by explanation.”

ADVERTISEMENT:

CONTINUE READING BELOW

If Cowdery has an equivalent in the UK’s political-philanthropic firmament it is Paul Marshall, the founder of the $80 billion Marshall Wace hedge fund who owns The Spectator, a conservative magazine, and is a shareholder in right-wing TV channel GB News and the Unherd website. Politically, they appear opposites, particularly on Brexit, which Marshall backed, but Cowdery says the two “frenemies” are closer than one might think.

“I’ve known Paul 20 years. We meet, we talk, we debate, we kiss, we leave. Paul and I would not be very far apart on our economic thoughts. We disagree about Brexit, but other than that, we’re both broadly capitalists who believe in liberal democracy,” he says. Marshall is devoutly Christian, whereas that is now in Cowdery’s past.

Paul Marshall, founder of the $80 billion Marshall Wace hedge fund. Photographer: Lam Yik/Bloomberg

Marshall, once a supporter of the Liberal Democrats, has moved to the right since Brexit. Cowdery says Marshall is driven by the belief that “culture creates the type of society we all enjoy, and that culture has become overly liberal.” He is “a sincere man, and sincerely wrong” on that, he adds. A source familiar with Marshall’s thinking responded that, while the two men are friends, nobody is perfect and it is a pity Cowdery has gone down a socialist-progressive route.

Labour links

Cowdery styles himself centre-left but insists Resolution is apolitical, an argument that is not easy to sell. The think tank’s first three chief executives, Sue Regan, Gavin Kelly and Bell, were special advisers to senior Labour Members of Parliament – Kelly and Bell to Labour leaders. Resolution’s new chief executive Ruth Curtice, a former Treasury civil servant, is its first boss not to be overtly political.

Cowdery points out that the think tank’s president David Willetts is a former Tory minister and advisory council member Eleanor Shawcross was former Conservative Prime Minister Rishi Sunak’s policy director. Less generous voices note that they represent a small minority at Queen Anne’s Gate.

It was a Tory, though, that gave Cowdery his crowning glory. In her first speech as Prime Minister after David Cameron resigned following the Brexit referendum in 2016, Theresa May chose to speak up for families who “just about manage.”

Cowdery was astonished a Conservative would focus on “a group of people that just 15 years earlier weren’t on the political map,” he says. “Our single greatest accomplishment is that people across the political spectrum now routinely talk about the squeezed middle.”

© 2025 Bloomberg

Follow Moneyweb’s in-depth finance and business news on WhatsApp here.

#ragstoriches #capitalist #Britains #influential #tank