Half a century ago, turmoil in the Middle East brought the global economy to its knees. Today, even as the region’s geopolitics grow more fractious, oil markets and central banks typically treat conflict as a shock to watch — not one that dictates the macro outlook. A 1970s-style energy crisis doesn’t look imminent. If it were to materialise, the consequences for inflation, growth and policy would be profound.

In this report, we present three broad paths for how Middle East shocks could play out — categorised by the expected response of oil markets—and assess their implications for the global economy. In the most extreme case, an escalation that hits energy infrastructure or key choke points would drive sustained price increases, reviving inflation risks and putting pressure on central banks to adopt a hawkish stance.

• A major regional escalation that targets energy infrastructure, such as that in Saudi Arabia or Iraq, or critical choke points, such as the Strait of Hormuz, would break the market’s assumption that oil keeps flowing.

• Oil prices could surge as much as 80%. As of early 2026 that would mean a climb from $60 to as high as $108. For the global economy that would mean slower growth, higher inflation and more hawkish monetary policy.

• In our base case, a renewed flare-up centred on Iran, Iraq or the Persian Gulf could still produce sharp but short-lived moves—assuming conflict stops short of causing prolonged damage to energy facilities. Oil prices may spike briefly before returning to baseline.

• Limited shocks, or instability distant from major oil sites, would leave physical supply largely intact and prices unaffected. The war in Gaza is a striking, and heartbreaking, example of a major geopolitical shock that has left basically zero imprint on global oil markets.

What happens here doesn’t stay here

From oil price spikes to the diversion of shipping routes and refugee flows, what happens in the Middle East doesn’t always stay in the Middle East. The region supplies three inputs to the world: energy, capital and trade routes.

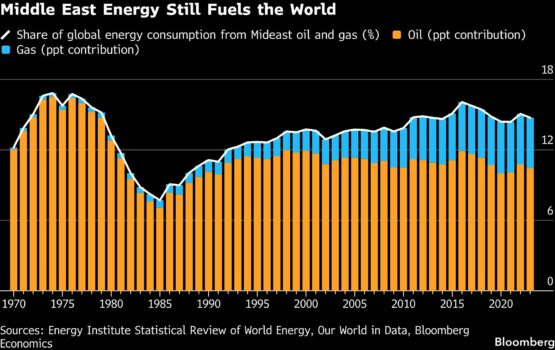

Despite the rise of renewables and the US shale oil revolution, the Middle East still fuels the world. It pumps a third of global oil, a fifth of gas and, just like in the 1970s, meets 15% of total energy needs.

Four of the world’s top 10 sovereign wealth funds are from the region, those belonging to Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. Their holdings include American tech companies, English football clubs, Egyptian real estate, African mines and Turkish bank deposits.

The Middle East anchors global commerce through trade routes. The Strait of Hormuz carries one-fifth of world oil flows. The Red Sea and the Suez Canal are important trade routes between Asia and Europe. Projects such as the India-Middle East-Europe Corridor, Iraq’s Development Road and China’s Belt and Road promise to expand this network.

All this means the Middle East remains vital to global stability, energy security and the world economy.

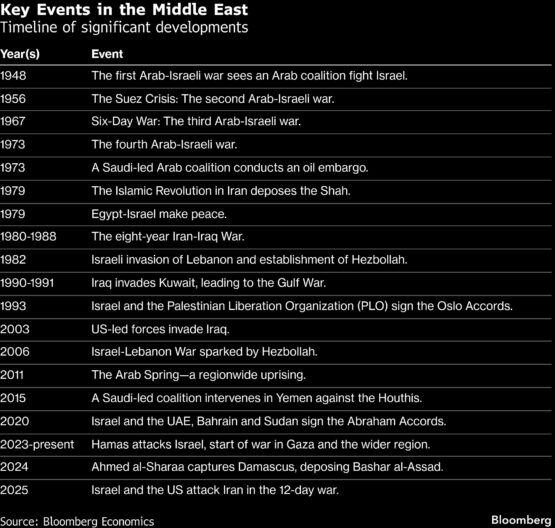

The Middle East’s history stretches back millennia. The geopolitical dynamics that govern it today have their roots in the post-World War II order, specifically in 1948. Since then, conflicts in the region have unfolded in two distinct phases.

The first phase runs from 1948 to 1979, when regional instability revolved around Arab-Israeli wars. The establishment of Israel in 1948 saw the beginning of tensions between the new country and its Arab neighbours that led to four wars, in 1948, 1956, 1967 and 1973.

This period also saw growing US interest and involvement in the region as old colonial powers such as Britain and France began to retreat. Initially, the US relied on what it called its “twin pillars” in the region to maintain stability: Iran and Saudi Arabia. But two events in 1979 changed that, marking the beginning of the second phase.

First, the Iranian revolution in 1979 turned Tehran from an ally of Israel’s to a fierce foe. Second, the Camp David peace treaty between Israel and Egypt neutralised the Arab world’s largest country. Since then, no war between an Arab state and Israel has taken place.

Instead, conflict has shifted to wars between Israel and new militant groups backed by Iran. These include Hezbollah in Lebanon, which emerged after the Israeli invasion of Beirut in 1982, and Hamas inthe Palestinian territories, which was established during the first intifada in 1987. Iran’s Axis of Resistance took full shape with the inclusion of Iraqi militias, formed in the aftermath of the American invasion of Baghdad in 2003; and the Houthi militants in Yemen, who rose to prominence after they took over the Yemeni capital in 2014.

Today, we may be witnessing the end of this second phase. After the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks, Israel has severely diminished Hamas and Hezbollah. Iran lost an ally with the toppling of Bashar al-Assad in Syria. And Tehran’s nuclear infrastructure and military capability suffered during US-aided Israeli strikes in the 12-day war.

As this second phase concludes, a new chapter will emerge, with new actors and likely more conflicts.

Changing alliances and new hot spots

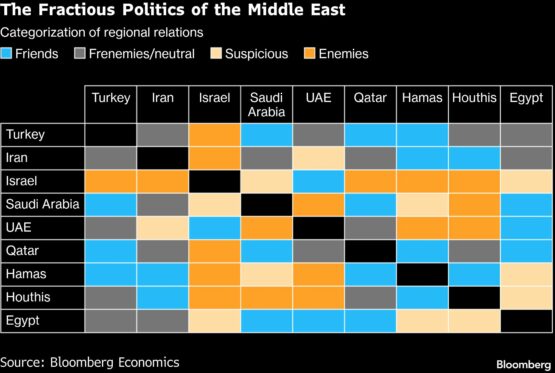

Today’s Middle East is made up of four blocs battling for control, with bloody fronts and high stakes.

• Iran and its axis: The alliance includes militias in Iraq, Hezbollah in Lebanon, Hamas in Gaza, the Houthis in Yemen and some other smaller groups. Tehran uses them to project influence and build forward defence. Successive waves of US sanctions have crippled Iran’s economy, but this hasn’t affected its ability to continue to prop up its partners in the region. Since 2023, Israel has weakened the axis considerably, mainly by targeting Hamas and Hezbollah leadership. The Houthis remain largely unscathed, despite their maritime campaign in the Red Sea. Iran continues to view its power erosion as a temporary setback, though it’s concerned about its ability to build the axis back up.

• Israel and the UAE: In 2020, the UAE and Israel signed the Abraham Accords, normalising their ties. Since then, Israel launched a war against Gaza in response to the Oct. 7 Hamas attacks. The war weakened Hamas and Hezbollah, which the UAE approved of, but Israel’s de facto annexation of the West Bank, coupled with the indiscriminate violence in Gaza, ruffled feathers in Abu Dhabi. Nevertheless, the UAE remains committed to this relationship. Israel, for its part, wants to use this moment to further weaken Iran and its nuclear program, while expanding the Accords to include countries such as Saudi Arabia, bypassing the Palestinian issue.

• Saudi Arabia: Riyadh is focused on the economy and its Vision 2030, which demands calm in the region. It restored diplomatic relations with Iran in 2023, reached a truce with the Houthis and is actively mediating conflicts elsewhere. A normalisation agreement with Israel is unlikely as long as it doesn’t include a path to a Palestinian state. Tensions with the UAE have escalated and reached a peak in Yemen, where each country supports opposing sides.

• The Turkey-Qatar alliance: In the 2011 Arab Spring protests, they backed Islamist candidates, including the Muslim Brotherhood, in Egypt, Syria and Libya. Turkey supported Qatar during the 2017 blockade led by Saudi Arabia and the UAE, and Qatar reciprocated with financial support in 2018. The fall of Assad in Syria is a win, though the decline of political Islam has dented their regional project. Importantly, both are now on good terms with Washington.

These four blocs are battling it out in four hot spots. Any of them could flare up anytime:

ADVERTISEMENT

CONTINUE READING BELOW

1. Gaza: After two years of war that flattened the strip, Hamas and Israel reached a ceasefire in October 2025. Still, Israel has continued to strike the enclave periodically, and little progress has been made to the next stage of the truce. Hamas must disarm, and Israel must withdraw. Neither side wants to do either. Without progress, the risk of a return to war is high.

2. The Levant: Near-daily Israeli strikes on Lebanon underscore that a ceasefire doesn’t mean peace. At home, the Lebanese government faces a choice: attempt to disarm Hezbollah and risk civil war, or avoid the issue and risk another conflict with Israel. Parliamentary elections due in May increase the odds of delay.

Israel is also conducting frequent incursions into Syria, though Damascus appears unwilling to match the escalation. The new leadership under Ahmed al-Sharaa, who took over in December 2024, is struggling to assert full control over the country as sectarian clashes periodically break out. He’s prioritising economic recovery: seeking sanctions relief — which US President Donald Trump seems willing to support—and attracting investment. While there’s been some progress, and the Syrian pound has strengthened, economic conditions remain fragile.

3. The Red Sea: In December 2023, Houthi attacks on passing vessels forced shipping companies to avoid the Strait of Bab al-Mandeb, a narrow maritime route linking the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean. Tensions have eased recently with a US-Houthi truce in May, Houthis signalling restraint if the Gaza ceasefire holds, and shipping companies floating a possible return. Despite this, shipping traffic through the area hasn’t returned to prewar levels, and it’s unlikely to, given the prospects for renewed conflict.

4. Iran-Israel: An unprecedented 12-day war launched by Israel in June, following months of missile exchanges between the two countries, damaged Iran’s nuclear program, left almost 1 000 dead, and exposed Iran’s vulnerability and Israeli penetration. Yet the leadership also framed it as resistance: “Our worst-case scenario played out, and we’re still standing. We even showed the Israelis we could reach them with our missiles,” an Iranian official told us. Importantly, Iran’s nuclear program wasn’t eliminated, its ballistic missiles remain a threat, and Tehran may double down by attempting to rebuild its proxies. Prediction markets put the odds of renewed direct strikes in the first half of 2026 at about 40%.

Domestic politics will also shape regional conflicts. Deteriorating economic conditions in Iran sparked large-scale protests starting in late December and early January. The prospect of a change in government in Tehran aligns with Israeli objectives, but it’s unclear whether that will be enough to stave off another round of the war. Meanwhile, Israel is due to hold its parliamentary elections by October 2026.

The Gulf Arab states are caught in the middle. Their main security guarantor, the US, backs Israel, now considered by most their primary threat. They’ve managed Iran, their traditional adversary, through containment and dialogue. But Tehran has made clear that if a war with Israel spirals, it could play its final card: striking regional energy infrastructure or closing the Strait of Hormuz.

Geopolitically, the stakes couldn’t be higher. Economically, the damage has so far remained local rather than global. More than two years of war in the Middle East have seen costs rise the closer you get to the heart of the conflict.

The war has devastated Gaza. The Israeli assault has damaged or destroyed more than 90% of residential buildings. The World Bank estimates the economy contracted 83% in 2024 and an additional 12% in the first quarter of 2025.

Israel’s output is running 5% lower than its prewar path. And the war may have left lasting scars. Some reservists won’t fully return to the job market. Brain drain is pushing talent abroad. Defence spending will rise for the foreseeable future. And foreign direct investment has slid from 5% of gross domestic product before the war to 3% since.

Egypt is piling up losses from the Suez Canal. Before the war, Egypt earned about $9 billion annually from the waterway. With traffic more than halved for almost two years, revenue has fallen by several billion.

The Military Balance in the Middle East

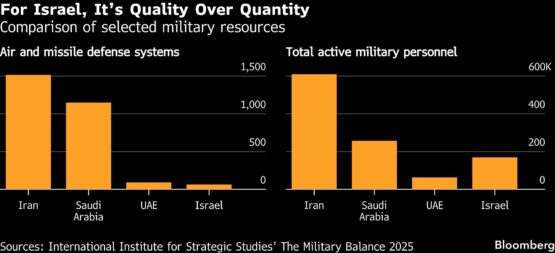

The strongest players in the Middle East are the US and Israel. With almost unlimited access to US weapons and military kits, Israel’s military is unrivalled, giving it a significant advantage and escalation dominance. Israel’s multilayered missile defence programme is instrumental in protecting it from rocket attacks from Gaza and Lebanon and, more recently, from Iranian ballistic missiles, but it isn’t infallible.

On the other end of the spectrum, Iran’s conventional weapons arsenal is limited after decades of arms embargoes and sanctions—though it has an ambitious ballistic missile program, which improved the size, diversity and precision of its arsenal. Its conventional shortcomings led Tehran to invest heavily in building relationships and networks in the region, creating its Axis of Resistance. Israel’s targeting of the Axis since 2023 has significantly degraded it, leaving Tehran in a vulnerable position.

Somewhere in the middle sit the Gulf Arab states. They’ve invested heavily in their armed forces — mainly through US-weapons purchases to build their ties to Washington, often focusing on big-ticket capabilities such as fighter jets and advanced air defences. The UAE has diversified its military relationships, building ties with China and European states, too. Saudi Arabia and the UAE are also investing in indigenous systems, but they remain limited. As of today, their armed forces are deployed mainly in the region and in Africa, and are no match for Israel’s superior capabilities.

This asymmetry hasn’t produced stability; instead, it has entrenched coercion over compromise and normalised the use of force, steadily eroded prior red lines and locked the region into cycles of asymmetric violence.

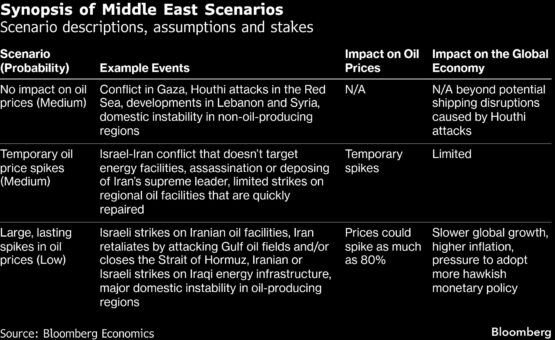

To date, multiple worst-case geopolitical scenarios for the region have materialised, but the effect on oil prices has been limited to nonexistent. Looking ahead, we group possible future Middle East shocks into three categories, based on their expected impact on oil prices.

Geopolitics and Oil Scenario 1: No Impact

Most geopolitical shocks don’t move oil prices, especially when they occur far from key oil fields in Iran, Iraq and the Gulf. The economic and oil market impact is usually limited. In this category, we include:

• The future of Gaza: Violations of the ceasefire have become the norm, with little prospect for progress toward a lasting peace. No matter if war resumes, the current uneasy status quo endures or mass cross-border displacement occurs, the human consequence may be severe, but the global economic impact will remain small.

• The Red Sea: Houthi attacks have further militarised regional waters, delivering strategic gains including global attention and increased regional support. That makes the campaign easy to restart if it suits them, leaving any return by shipping companies inherently risky. Whether the Houthis allow shipping to return to normal levels or not, oil flows will barely be affected.

• Lebanon and Syria: Oil prices are unlikely to react to whether they enter war with Israel, normalise relations, face government instability, descend into civil conflict or suffer the consequences of potential Israeli-Turkish clashes as the two increasingly face off in the region.

• Domestic instability in the wider region, such as the possibility of unrest in Jordan or Egypt, is also unlikely to move markets, since these countries import rather than produce oil.

Even in oil-rich countries, not all disruptions matter.

ADVERTISEMENT:

CONTINUE READING BELOW

Iran faces a perfect storm, both internally and externally. The impact of economic hardship and environmental crises is exacerbated by sanctions. Political and social pressure, worsened by threats from the Trump administration and Israel, adds to the stress on Tehran. Despite this, protests that don’t threaten the leadership, assassinations below the top echelon of power or minor breaches of its uneasy truce with Israel are unlikely to hit oil production. That was evident in the lead-up to, and aftermath of, the 12-day war.

During that war, Israel targeted some of Iran’s energy infrastructure, including the country’s oldest oil refinery. These hits were significant because they affected Iran’s domestic fuel supplies, but the impact on oil prices was limited because crude exports continued.

Iraq is Opec’s second-largest producer, after Saudi Arabia, and has long been an arena for US-Iran competition without a visible impact on oil. Attacks on US bases by Iran-allied proxies or Tehran itself, Israeli strikes on paramilitary units close to Iran, or assaults on northern oil and gas fields are unlikely to move markets—as long as they don’t disrupt energy facilities in the south.

This scenario — geopolitical escalation but not enough to shake oil markets—is our second-most likely. More likely, we think, is that things could move up a notch.

Scenario 2: Temporary Oil Price Spikes

The second category, and the one we see as most likely, includes scenarios in which geopolitical events in Iran, Iraq or the Gulf—the main oil producers—cause oil prices to spike but only briefly. Examples include:

• Trump may have brokered a ceasefire between Iran and Israel after 12 days of war, but the drivers of that conflict haven’t disappeared. Another round of conflict, at some stage, appears likely. If war resumes but remains limited, without escalating to target regional energy facilities, then any oil spike would likely be temporary. If the Houthis resume their campaign in the Red Sea in support of Iran, the impact on regional shipping is likely to be more long term.

• Iranian Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei is ageing. The war highlighted the threats to his life, and the latest round of protests underscored just how tenuous his hold on power is. The assassination or deposing of Iran’s supreme leader would be a major geopolitical shock that might jolt oil prices, but with an impact that would likely be short-lived. The system would quickly appoint and rally behind a successor, ensuring continuity.

• Attacks on oil facilities in the Gulf or Iraq that are surgical but disrupt output, even in large quantities, can have only a limited impact on prices if the production facilities are quickly repaired and brought online. The 2019 attack on Saudi oil sites, which briefly took half of its production offline, is a recent example.

We see some combination of events in this category occurring as the most likely scenario. The Iran-Israel truce is fragile, influential factions in Israeli politics favour continued conflict, and there’s no deal on Iran’s nuclear program. Explicit threats against Iran’s leadership and, if they’re carried out, the likely retaliation from Tehran suggest escalation is a real risk.

Scenario 3: Large, Lasting Spikes in Oil Prices

In this category, the geopolitical shocks are major and the impact on energy prices significant.

Israel could strike Iran’s oil facilities in a bid to escalate during another round of direct attacks. Should this happen, Iran could retaliate by hitting oil fields in the Gulf, something it has threatened to do in the past. If the damage is such that it’s impossible to bring production back online rapidly, oil prices will be affected in the long run.

Iran has for years threatened to close the Strait of Hormuz—through which one-fifth of the world’s oil supply flows—when pressures mounted. It has never acted, but if cornered in a renewed war, Tehran could finally follow through, even at the cost of its own exports. Removing one-fifth of global supply would have a significant and lasting impact on oil prices.

What would it take for Iran to take that step? We think three conditions would need to hold simultaneously:

1. US strikes Iran while nationwide protests rage, and the system faces existential pressure. Tehran might tolerate cyberwarfare, blockades or jamming that weakens its security networks. But when domestic revolt collides with foreign attacks, leaders may lash out — betting that external confrontation can smother internal instability.

2. Iran maintains its ability to strike. Tehran’s capabilities have weakened over the past two years — proxies have diminished, missiles are depleted, and air defences are damaged. If the US strikes and spares the remaining arsenal, or fails to trigger a coup, willingness and capability could recombine with destabilising force.

3. Decision-makers are united. For now, Tehran is stunned—worried about what might come, and stuck in an internal debate over whether to back down and deal with Trump or dig in their heels. If that paralysis lasts, it could blunt their reaction.

Other scenarios that could result in large, lasting spikes in oil prices include the targeting of Iraq’s energy infrastructure, by either Iran or Israel. Iraq exports around 3.5 million barrels per day, or about 3% of global oil supplies. Most of that flows through a port in the south to the Gulf, with the remainder via a pipeline to Turkey. An attack on southern facilities could take a large share of Iraqi oil offline.

Political instability and discontent in the Middle East have been a long-lasting issue. Today many of the drivers of the 2011 Arab Spring—poor governance, lack of opportunities and wealth inequality—remain. Should large-scale protests occur in oil-rich countries, like Iraq or, less likely, one of the Gulf states, they could undermine political stability and disrupt oil and gas output.

Those would be major shocks. The region supplies roughly one-third of global oil and one-fifth of the world’s natural gas. Taking a chunk of that output offline would create a price shock far greater than the supply loss itself. It isn’t unthinkable that oil could nearly double in price, as occurred after Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait.

This is our least likely scenario. Even when conflict has broken out, all sides seem to be sparing energy facilities, partly out of self-interest and partly to avoid crossing Trump, who wants lower oil prices.

How Does Oil Jump When Barrels Vanish?

Losing oil barrels pushes prices higher—the law of supply and demand makes that inevitable. The harder question is determining the magnitude of the impact. We mine past disruptions, academic studies and prediction markets to pin it down. Our conclusion: A 1% supply loss lifts prices by 2% to 6%, with a midpoint of 4%.

Applying that to some potential risks: Iran is a major producer, facing popular unrest and possible US or Israeli strikes. It supplies about 3% of global crude output, so disruptions there can deliver a sizable price punch. At current prices a full hit risks about $7 per barrel, even before a fear premium kicks in.

ADVERTISEMENT:

CONTINUE READING BELOW

If the war spreads across the Middle East from Iran, more barrels could be at risk. A disruption at the Strait of Hormuz would choke about one-fifth of global oil flows. That shock, though unlikely, would push crude to about $108 per barrel, from $60 as of the beginning of 2026.

To gauge oil’s price reaction to output shocks, we study historical surprises. To filter out noise, we require that each event in our sample must have been unexpected, affect supply but not demand and move prices immediately. The three cases below meet those criteria. They offer a disciplined ballpark estimate, not an exhaustive catalogue.

• The attack on Saudi oil facilities in 2019: On Sept. 14 a Houthi drone struck Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure and knocked 5.7 million barrels per day offline instantly, equating to about 5% of global oil supply. As a result, oil prices jumped by about $9 per barrel to $69, or roughly 15%. That implies a price multiple of around 3 times the size of the disruption.

• The Trump-mediated Saudi-Russia deal in 2020: On April 2, in the middle of the pandemic, President Trump mediated between Russian President Vladimir Putin and Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to curb oil supplies as prices fell to $25 per barrel. OPEC+ ended up reducing output by 10 million barrels per day, about 10% of global supply. Oil prices rallied to $34 per barrel, a 36% jump. That implies a price multiple of 3.6 times the size of the cuts.

• OPEC+ cuts in 2022: Less than three months after then-US President Joe Biden visited Saudi Arabia to ask for higher output in the aftermath of the Russia-Ukraine war, the kingdom and its OPEC+ allies delivered the opposite of what he requested. On Oct. 5, OPEC+ agreed to reduce output by 2 million barrels per day. Markets had expected cuts of about 0.5 million barrels per day. The surprise was therefore 1.5 million barrels per day, roughly 1.5% of global supply. Prices rose by $6 per barrel to $94, a gain of 6.8%. That suggests a price multiple of 4.5 times the size of the cuts.

Academic studies estimate that price responsiveness to supply shocks ranges from 2 to 6 times the size of the shock. They also help understand the dynamics at work. A supply outage creates shortages: Consumers want to use more oil than is available, pushing up prices. Higher prices attract new supply but also destroy some demand. The post-shock price depends on how price-sensitive demand and supply are.

A third way to gauge oil price responsiveness to supply outages is to look at expected disruptions through prediction markets. The Iran-Israel war in June offers one such example. Prediction markets priced in an expected global oil supply loss of around 8% at the height of the war, reflecting the risk of a Strait of Hormuz closure. But actual oil prices surged by about a fifth over the same period. That implies a price reaction of roughly 2.5 times the size of the expected supply hit.

Other factors also shape how prices respond to supply shocks, including inventory levels and the duration of outages. These can shift the multiplier within the range and, at times, even push it outside.

Who wins, who loses from a major oil spike

In a worst-case scenario, closing Hormuz removes roughly one-fifth of global oil supply. Such a sudden shortage would overwhelm buffers, forcing prices to rise sharply. Our estimates from history and other studies imply an 80% surge in crude. From $60 in early 2026, that shock would drive crude toward $108 per barrel.

The economic damage from $100-plus oil is likely to be smaller than during past oil shocks, for two reasons. First, economies are less oil-intensive than in the past. In the US, the amount of oil needed to produce one unit of GDP has fallen by about a quarter since 2011. Second, inflation means $100 oil today buys fewer goods and services than $100 oil a decade or two ago. But it’s still a shock, and different parts of the world will feel it differently.

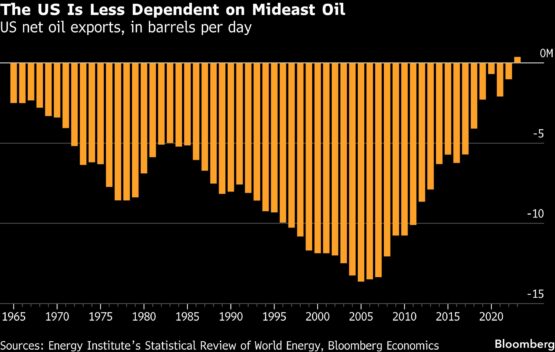

For the world’s largest economy, oil shocks no longer hit like they once did. Shale turned America from a major importer during the Iraq War era into an exporter. That shift will cushion growth when crude prices spike, meaning the impact will be close to neutral for the US.

This doesn’t mean more expensive oil will be popular. The price spike will benefit a segment of the American economy, namely oil producers. For other corporates, energy is a cost they’ll have to foot. And for consumers, a higher fuel bill leaves them with less cash to spend on other items.

Feeding $108 oil into Bloomberg’s SHOK model suggests US inflation could climb toward 4%. Central banks would normally look through such shocks, but the risk of unanchored expectations could force a more hawkish stance. A new Federal Reserve chair would face that trade-off as Trump may exert pressure for lower rates.

The US may absorb higher energy prices through inflation, without paying in growth. Other major economies are less fortunate.

That applies to China, the world’s largest crude importer. Beijing is the biggest buyer of Middle Eastern oil, the largest purchaser of discounted Iranian oil and the most dependent on energy transiting through the Strait of Hormuz. Plugging $108 oil into our SHOK model for China flags a hit to growth in the year ahead of about 0.5 percentage point in 2026 and a boost to inflation of also about 0.5 percentage point.

It also applies to the euro area. Using SHOK we find that $108 oil would send inflation above 3% and drag 2026 growth by about 0.5 percentage point. That would leave the European Central Bank facing a difficult choice: lower rates to support growth or raise them to tame inflation.

For developing economies, how oil shocks hit currencies is of first-order importance. Exchange rates shape inflation, growth paths and consumer confidence. A rally in oil prices benefits producing countries—like Colombia, Nigeria and Russia—at the expense of importing nations, such as India, Indonesia and South Korea.

The Middle East is home to some of the world’s largest oil exporters: Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UAE and Kuwait. Normally these economies gain from oil rallies. But if prices surge because of disruption in their own exports, the windfall evaporates.

For some Middle Eastern countries, the shock would be a double whammy. Rising geopolitical risks threaten external security, while lost oil revenue weakens domestic stability. Shrinking income erodes the oil-funded “benefits for compliance” social contract. External pressure would collide with internal fragility, amplifying political instability risks.

For regional energy companies such as Saudi Aramco, Adnoc and QatarEnergy, Bloomberg Intelligence assesses that the impact of Middle East conflict depends not only on how oil and gas prices move, but also—crucially—on whether production and exports remain uninterrupted. When geopolitical tensions lift prices without disrupting Gulf supply, the effect is clearly positive.

At current output of around 10 million barrels per day, Aramco operates at a scale where a $10-per-barrel move in oil prices is worth roughly $35 billion to $40 billion a year in additional revenue (before fiscal take), implying a very large uplift to cash flows as long as production and exports are uninterrupted.

For Adnoc, currently producing roughly 3.6 million barrels per day, the same price move implies a smaller yet still-significant revenue gain at roughly $13 billion a year. QatarEnergy, which supplies roughly one-fifth of global liquefied natural gas, is less sensitive to short-term price spikes because most of its sales are under long-term, oil-linked contracts, but it still benefits over time as higher oil prices feed through to contract repricing—provided exports continue.

The picture deteriorates when price spikes are driven by disruptions inside the region itself. Damage to production facilities, export terminals or shipping routes, including the Strait of Hormuz, could sharply reduce realised sales even as global prices surge. In such cases, crude at $100 or more offers little comfort as barrels or LNG cargoes cannot be shipped, insured or paid for.

Even short-lived disruptions tend to leave a lasting mark on these companies’ valuations as investors reprice security and infrastructure risk. Governments often lean more heavily on national energy companies during periods of stress, diluting returns to minority shareholders. Middle East conflicts may be bullish for energy prices—yet for regional producers, they’re positive only if oil and gas keep flowing.

Since Hamas’ 2023 attack on Israel, Middle Eastern geopolitics and global oil prices have, in general, moved on separate trajectories. If the worst-case scenario unfolds, the firewall shielding energy markets from geopolitics could collapse—and the ghosts of the 1970s may come back to haunt the world. For now we expect Middle Eastern geopolitics to remain highly volatile, while energy markets stay comparatively insulated.

© 2026 Bloomberg

Follow Moneyweb’s in-depth finance and business news on WhatsApp here.

#oil #war #Middle #East #crash #world #economy